Thanks to the generosity of my friend Corky who shared her house for the weekend, I went on a writing retreat with three friends. We all write poetry, and some of us write prose, too.

When we all arrived, we talked about our goals for the weekend, and then we set up a schedule for the day. It’s a good thing some of us are task-oriented, unlike me, the scatter-brain.

Today’s schedule started with private writing time for three hours on projects of our choice. After this, we came together to talk about how that went. Hearing everyone’s thoughts on what they’d accomplished helped me to see what I’d accomplished, and it helped us all to create another set of goals for the next round of writing later in the day.

Other activities in our schedule include reading poems aloud for inspiration, using a prompt to create lines for a collaborative poem, and a formal feedback session where we’ll share some work we produce here.

Writing retreats can be very productive times, especially for people working on particular projects, like a memoir. Without the distractions of my home, my garden, my husband, my dogs, I have no excuse not to write.

For some people, being in a beautiful place is inspiring. For others, it can be distracting. Corky is lucky to live on a small lake in North Central Florida, so the view is inspiring for me. I love North Florida more than I love jelly donuts. But because I live in this area too, it’s not so unfamiliar to me that I feel I have to get out and explore.

Writing retreats can take many forms. I’ve done the “staycation” retreat when my husband is out of town, hunkering down by myself in my home with a writing goal in mind. Those have not always been as successful as I’d hoped in terms of production. Those darn distractions. I know I’ve hit rock bottom when I find myself cleaning the bathroom instead of writing.

Writing retreats taken away from home can eliminate those distractions. One year, I went to a motel with my friend Sandra. We had separate rooms, and we got together for lunch and dinner, again to discuss our progress and goals. Having a time to meet with another writer gave me a sense of accountability.

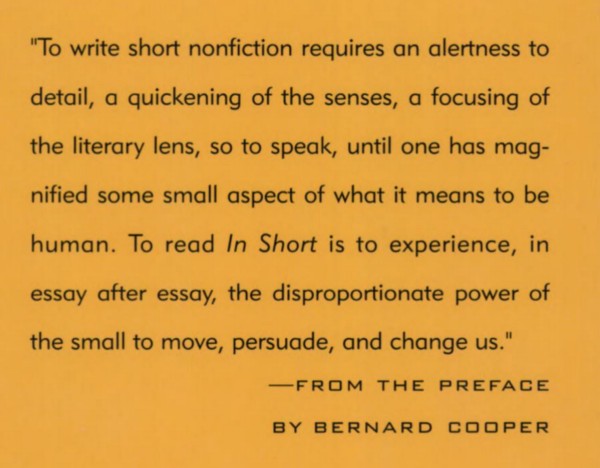

Some of my writing friends have gone on retreats that are managed by writing teachers or coaches. These sometimes include workshops or seminars on particular topics. An example of that is the Iota conference retreat that focuses on very short nonfiction. It’s held in the beautiful downeast region of Maine.

Of course, you have to be able to afford those professionally managed retreats, or get a scholarship to attend one. If you can’t, going off with a few friends seems to be a good solution. You can have time to write, accountability, inspiration, and positive feedback and camaraderie.

Some elements of a successful group writing retreat include:

- Private time for writing

- Time for reading inspirational work, either in a group or individually

- Using prompts to create new work

- Formal feedback sessions to share work produced on the retreat

- Comfortable accommodations, either at home or away

- Accountability

Food and drink are required too, of course. If possible, it’s also helpful to have a mascot to bring good luck, or a familiar, or a spirit companion. We’ve been fortunate to be visited by these sandhill cranes.