First up, warm praise for a reading method new to me in 2024: slow reading.

Like the slow food movement, slow reading encourages the practice of attentiveness to the moment. I may have achieved dog-consciousness as a slow reader.

As a happy 2024 follower of the Footnotes and Tangents slow read of War and Peace, one chapter a day of this humane novel brought me all the pleasures of a well-plotted story, plus unexpected insights into human nature and history. The book has gobs of contemporary political and emotional relevance, and the international reading community’s commentary and extra info provided by leader Simon Haisell is a treat. For a busy person who wants to maintain a daily reading practice, consider a subscription to one of the many slow read offerings out there on the benevolent side of the internet. I wholly recommend Simon’s several 2025 offerings as he is well-informed about the books he chooses, he has an international following of readers who encourage friendly, diverse discussion of the books, and he is an excellent, reliable manager. I’m participating in the Wolf Hall Trilogy slow read this year.

Here’s some thoughts on the best books I read in the summer of 2024, and the kinds of readers who might appreciate those books.

The most unusual book of the summer for me was How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures by queer science journalist Sabrina Imbler, who juxtaposes their own growing up story with the stories of unusual marine organisms. The result is a series of stunning extended metaphors that undulate between the wonders of underwater life and the wonders of human consciousness. An excellent selection for readers who enjoy nature writing, magical metaphors, and the macro-micro entanglement of the big world and the individual psyche.

Double trouble: I read one book — Find Me — by Floridian Laura van den Berg and immediately requested another — State of Paradise — from my library. Both are quirky stories with low-key incorporation of supranatural events. Both books have an original voice, an original premise, and a full-throttle plot, and are great choices for those who love Florida in all its other-worldly diversity.

I’d never heard the name “Miranda July” before picking up All Fours, so the book must have been endorsed by a credible-to-me person somewhere on the benevolent internet. The narrator is perimenopausal, which was its own special delight. The book probably struck me as particularly imaginative because I knew nothing about the author while reading it. The plot is compelling, and the sex scenes are detailed, diverse, and hot, hot, hot. Read this book if you love sex.

Liars by Sarah Manguso was recommended by Lyz Lenz in her crucial yet hilarious stack, Men Yell at Me. I know I stayed up past my bedtime reading Liars because it had a propulsive plot, but I can’t remember a fucking thing about it beyond that. Probably says more about me than about the book. A good choice for those interested in the state of American cis/het marriage and books meant to be read at an astonishing speed.

In her memoir Wishing for Snow, Minrose Gwin writes of growing up with and rediscovering her schizophrenic poet mother, Erin Taylor. Closely observed on internal and external levels, the book is strikingly honest, and it incorporates many of Erin Taylor’s poems. Gwin is new to me, and I’m planning to read more of her graceful work. Read this memoir for the beauty of its language and to know more about mother/daughter relationships, schizophrenia, and poetry.

Consent by Jill Ciment reviews and revises her first memoir, Half a Life. Why? Because the first one didn’t sufficiently interrogate her relationship with and marriage to artist Arnold Mesches. The couple met when Mesches was a 40-something married man with kids and Ciment was his 17-year old art student in a situation that would be described today as sketchy in terms of the power dynamics. Ciment is such an authorial powerhouse in both memoirs, though, that the question of consent is nuanced and perhaps unanswerable. A book for anyone who enjoys or needs the skill of accepting opposing versions of reality.

Jane Satterfield’s phenomenal poetry collection, The Badass Brontës, is a must read (IMHO) for all Brontëphiles. Satterfield writes of her own encounters with Brontë texts, as well as how she imagines interactions among and between sisters Charlotte, Emily, and Anne, both in the past and in a time-optional afterlife. The surprising rhythms of the poems demand attentiveness, like curveballs and reversals in any context do. Perfect for poetry lovers and anyone fascinated by the Brontës.

Jesmyn Ward’s most daring book so far, Let Us Descend, is a book that makes me wish for a long enough life to read everything she will write in the future. It’s daring in the steps it takes into the spirit world, in its visceral detail of the suffering of enslaved people, and in the cascades of inter-related images it uses like a net of jewels to gather the best parts of being human. I read it first in February of 2024 and again over the summer. Everyone should read this book for its power, beauty, and humanity, and, given our in our current world situation, for its combination of cleansing rage and miraculous compassion.

If you like to buck trends, consider reading a memoir, since the powers-that-be never tire of telling us that memoirs are hard to sell. This year, I interviewed two authors with memoirs that came out in 2024, and I recommend both.

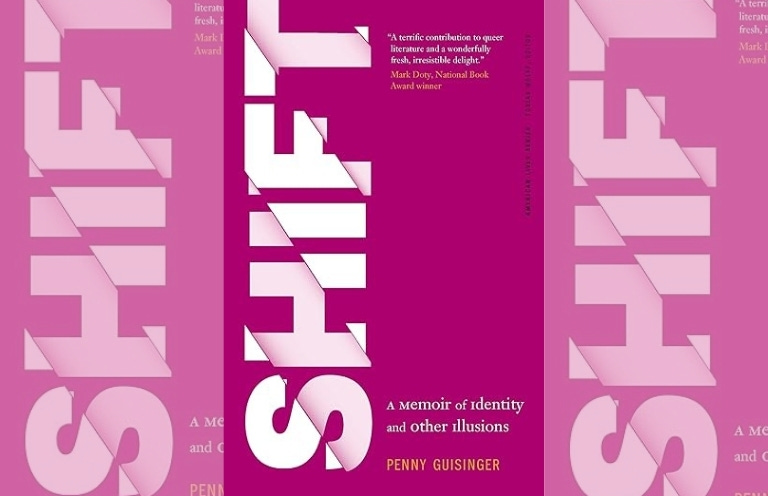

Penny Guisinger’s SHIFT: A Memoir of Identity and Other Illusions explores the power of change in the physical, emotional, and political shifts that occur within (and outside of) the memoir. Gusinger fell in love with a woman in her Downeast Maine community, ended her heterosexual marriage, and continued to parent her two children, who were quite young, and to work in a high stress job. The shifts required to make all this happen are set against the tumultuous context of Maine’s on-again-off-again Marriage Rights saga from 2011 — 2013. It’s also filled with that subtle Maine humor:

“I had a beer bottle wedged into a mesh cup holder hanging below the arm of my chair. I got right to work peeling the label from the exposed section of glass. I stayed on task throughout the conversation.”

Who hasn’t peeled a label off a sweating bottle during a hot, high stakes moment? This understated humor is one of the many elements in SHIFT that captured my heart. The book is also an intellectual treat, examining non-linear time in the context of personal and political “shifts,” including coming out as lesbian.

The book’s haunting relevance to the past decade’s Twilight Zone attacks on individual rights across the United States makes it a must read for understanding the current American political moment. Penny and her wife Kara lived through the approval and subsequent repeal of marriage rights on the state level in Maine. Their courage in managing their personal, family, and professional lives in the shadows cast by the bullshit repeal is just the sort of stubbornness so many of us need now.

SHIFT is a rare confluence of passion, humor, politics, and personal insight. Highly recommend. For more about the book, check out my interview with Penny in CRAFT.

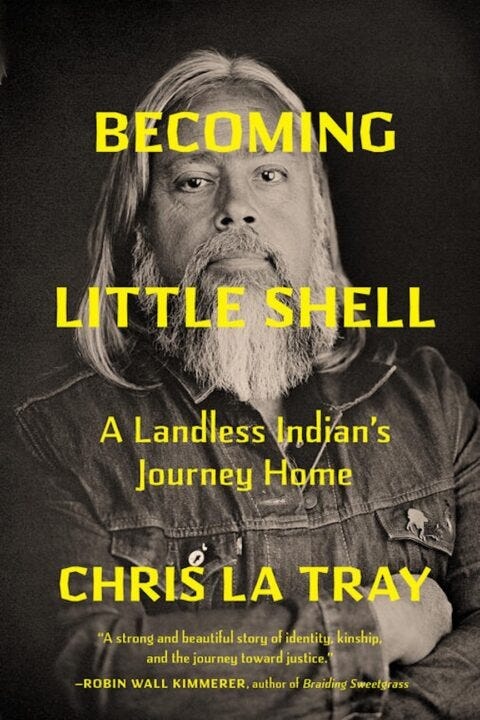

In Chris La Tray’s memoir Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home, the recovery of the Chippewa identity his father hid happens as the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians endures the long process of achieving Federal restoration. The search for a hidden personal past is juxtaposed with political demands for restoration of a historical past. The memoir’s scale is vast, and readers will come away with insights into Chris’s struggles and the struggles of his tribe, and others, against the colonial violence and machinery of the United States. For more about this remarkable memoir, check out my essay/review for On the Seawall.

There’s much to learn from this book about the many paths resistance may take, about respect for others’ choices, and about the recursive nature of oppression. Plus, the book is a beautiful love poem (Chris is currently the Poet Laureate of Montana) to the High Plains region.

Wishing you a radical year of reading!