And why should I read outside of my comfort zone?

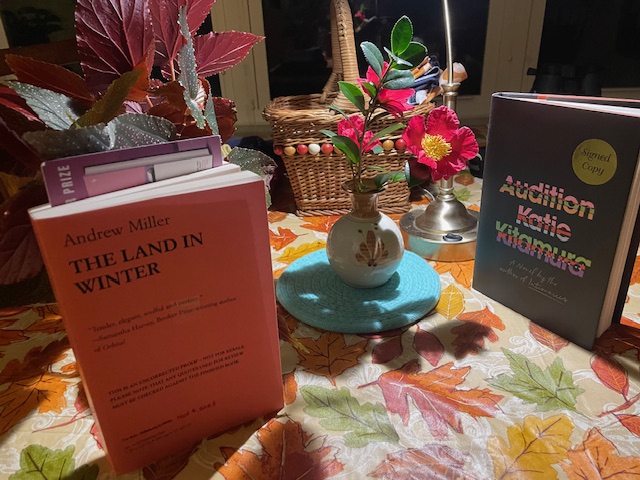

I’ve only read two titles on the Booker Prize short list, The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller and Audition by Katie Kitamura, so there’ no telling which book will win from my perspective. It’s the big night!

Audition was a First Editions Book Club pick at my local bookstore, The Lynx, a project spearheaded by writer Lauren Groff. The Lynx has been around now for a couple of years and its brick-and-mortar storefront and patio have added so much to cultural and social life in Gainesville, Florida. And, of course, Lauren and her team are fabulous curators, holding frequent book club meetings, author events, and writing classes.

Audition is not “my sort of book” for a few reasons — it’s based in NYC, the setting for too many novels IMHO, the prose is crisp and unadorned, and its protagonist has respect for psychiatry. But it is “my sort of book” for other reasons — its protagonist is a woman and the whole second half of the book is a killer plot twist. The book is, for a dinosaur-brain like mine, experimental and a bit inaccessible, but it was still a compulsive read. Once I got to the second half, I couldn’t put it down. And, It has things to say about motherhood that seem unique in literature to me, except that I never read books about motherhood, so how would I know?

The Land in Winter came to me via Autumn Toennis, a writer and an editor at Europa Editions who sent an ARC (advance review copy — because I write reviews, publishers often send ARCs to lucky me) with a note that said “Andrew doesn’t waste a sentence.” She’s right about that. Every sentence contributes to the plot, characterization, setting, or themes, but the prose is also elegant, even delicious. It’s a historical novel, set in England in the 1960’s during a brutal winter. As a Boomer, I resisted the idea that the 1960’s are so long ago they are historical. Reading it, though, was like diving into a not-too-cold pool. The opening propelled me underwater through the deep end and into a place of rest, where I could float on my back and look up at the clouds. It’s a novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch’s finest work, where characters interact with each other on deep levels even when they are hiding truths from each other.

The Land in Winter is not “my sort of book” because it’s written by a man. Decades ago, I began avoiding contemporary fiction written by men because of my irritation at the inevitable misogyny. So many books, so little time, as you know. As a young reader I excused favorite 19th century writers like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky for their patriarchal alignments because they came from a different time. Kind of silly, right?

I recommend letting others choose your books sometimes. As it turned out, The Land in Winter is exactly my kind of book: that restrained, elegant British tone, that peculiar British humor, the stiff upper lip characters with tormented psyches, and a sense of land that is conscious of its own history.

So, which book won the 2025 Man Booker prize? Find out here.