2. Jane Eyre

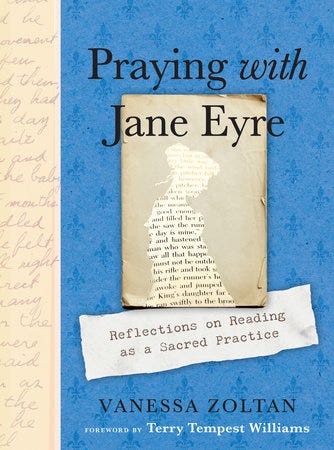

Down some internet rabbit hole, I saw the title Praying with Jane Eyre: Reflections on Reading as a Sacred Practice. I will read almost anything about Jane Eyre, and when a quick browse revealed that Praying with Jane Eyre was written by Vanessa Zoltan, a Jewish atheist, I was relieved. Fundamentalist religion pasted on top of literature irritates me. On to my library’s database!

I first held Jane Eyre as a chronically ill child confined to bed, a girl who’d read every book in the house and whined for more. My adoptive mother drove to the local library. There, she asked for help from a miraculous but anonymous-to-me librarian who ended up having the most lasting and positive influence on my childhood.

[Please thank a librarian today, especially if you live in a state that’s under pressure from self-righteous book-banning organizations.]

Praying with Jane Eyre is a combination of memoir, sermon, and literary criticism. I couldn’t stop reading it, even though there’s a bit too much concrete spirituality for me in it, and I disagree with some of Zoltan’s opinions about the novel (the Reeds never deliberately tortured Jane? Please). Still, it’s Jane-adjacent, which I cannot resist, and Zoltan make many meaningful observations about Judaism, Atheism, the epigenetic impacts of the Holocaust (all four of her grandparents were Holocaust survivors), and the process of re-reading. Believing that re-reading can be a sacred act, she has this to say about faith and re-reading:

“what I came to mean by faith was that . . . the more time you spent with the text, the more gifts it would give you.” Even when “you realized it was racist and patriarchal in ways you hadn’t noticed when you were fifteen or twenty or twenty-five, you were still spending sacred time with the book.”

Honestly, I’m not clear on the idea of sacred time. Is it like when I take to the bed all day with a book? Is it like Mary Oliver paying close attention during her morning walks? Or is it about repetition? Or all of these?

Is sacred time forgiveness time? Is it a deliberate disregard for perfection? Most, maybe all, nineteenth century European literature is racist and patriarchal. Charlotte Brontë was not a feminist saint. But her most famous book is more than the sum of her writerly parts, maybe because she trusted in the magic of her unconscious. If she was stuck, as a writer, she asked her own dreams for help and illumination before falling asleep at night.

That’s the quality I most admired about Jane when first reading the book: she trusted her own mind, both the conscious and the unconscious parts. She was self-reliant.

Since childhood, I’ve re-read Jane Eyre yearly. There must have been skipped years, but since my obsession began at eight years old and I’m now sixty-six, I’ve probably read it fifty times. With each re-reading, the world of the novel is somehow made at once new and familiar.

How is it made new? Partly by what I notice. Children are the ultimate underdogs, and as a child, I noticed my own powerlessness as bitterly as Jane notices her powerlessness in the novel. As a teenager in a Karl Marx phase, I noticed the novel’s class struggles. In my early twenties, a second wave feminism phase, I noticed the caging of Bertha Mason.

Time can make a book new, too, if one’s well of compassion for others varies. Imagine my shock during my last re-reading when I felt compassion for the odious Mrs. Reed, that bad, hard-hearted, and mean substitute parent. Before that, even when my beloved Jane insisted on compassion for Mrs. Reed, I’d resisted. A year has passed, only a year, but I feel exponentially older and crabbier. I expect to have the pleasure of detesting Mrs. Reed again soon. It’s time.

In 2024, I’ll be joining a slow-read re-reading of War and Peace, a book I haven’t read for . . . let’s just say decades since I can’t recall exactly. Organized and hosted by Simon Haisell on Footnotes and Tangents, this will be my first experience of a slow-read and a communal internet read.

Maybe next summer I’ll host a slow read of Jane Eyre. Meanwhile I recommend the Rosenbach Museum’s free and streaming series “Sundays with Jane Eyre,” which covers satisfying chunks of the novel via discussions with Eyreheads from around the world.